Afghanistan’s Torkham border crossing with Pakistan is the country’s busiest. Nestled between imposing mountains on either side with nothing but stony outcroppings for as far as the eye can see, the bustling highway is an economic lifeline for a country that continues to struggle with a violent insurgency.

The road to Jalalabad is lined with a thriving market that sells everything from vegetables to used car parts from half a world away. Approaching the crenellated post that signifies the end of Afghanistan and the entry into Pakistan, towering, rainbow colored lorries ply the road alongside men pushing barrows filled with all sorts of merchandise and - not infrequently - family members.

From the opposite direction a slow parade of men, women and children are reluctantly returning home. Some to a country they barely know after decades spent in an exile, which for some began in 1979 when the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan.

Many are “undocumented Afghan returnees”, some of the 1.5 million of whom reside in the border regions within Pakistan’s tribal areas. They hold identity documents from neither Afghanistan nor Pakistan, nor do they have refugee status in Pakistan.

They are increasingly coming under pressure from local authorities to return home leaving them with little choice but to take the tortuous decision to exit their adopted country and enter into the unknown where they may or may not have relatives who can help bridge the transition to life back ‘home’.

From January to June 2016 only 33,000 undocumented Afghans chose to make this journey from Pakistan but in July alone a further 29,000 people crossed the border. In August, this number rocketed to nearly 70,000 additional arrivals.

The week of 18-24 September saw one of the highest number of returnees this year with over 11,000 persons crossing the frontier. IOM’s mission in Afghanistan is projecting that as many as 407,000 returnees may come back by 31 December 2016.

Many are coming with next to no possessions after travel made in haste. Others have managed to demolish their homes and pack rented trucks sky-high to the point of tipping over with building supplies, livestock, food and personal possessions with family members riding on the pinnacle of these jaw-dropping moving mountains.

On 21 September, IOM together with UNICEF, OCHA, UNHCR and WFP led a joint assessment mission to the border area. IOM is the lead agency providing services and post-arrival assistance to the most vulnerable undocumented Afghan returnees.

Chenoor Gul, 75, has a long white beard, a tanned face and impressive hands that speak volumes about a life that has been hard fought. Fleeing his home in the late 1970s in the midst of the war against the Soviets, Chenoor built a life over 45 years spent in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

He’s always worked as a daily labourer to support his three sons, wife and more recently a new grandchild. A series of nighttime raids over the past two months by police forces convinced him it wasn’t safe to stay any longer. He broke up his simple home and put together what possessions he could before paying the USD 300 – a fortune to him – to hire a truck and cross the border.

(Chenoor Gul left Pakistan with little choice. At 75 years old he must now provide for his family in a whole new environment and a country he hasn’t visited in 45 years. September 2016. Photo credit: ©N Bishop/IOM 2016.)

“I have nothing in Afghanistan - no land, no family - I am a stranger here but I will do my best to start a new life for my family. We want to live in dignity.” Chenoor repeatedly shakes his head and removes his turban emphasizing his sense of hopelessness.

Chenoor is fortunate that he has been able to bring some supplies with him but his wife suffers from hypertension and he expresses concerns about being able to care for her while seeking shelter in a land which is foreign to his children.

(Chenoor Gul’s three sons riding atop all their worldly possessions in a rental truck at the Torkham border crossing on 21 September 2016. Photo credit: ©N Bishop/IOM 2016.)

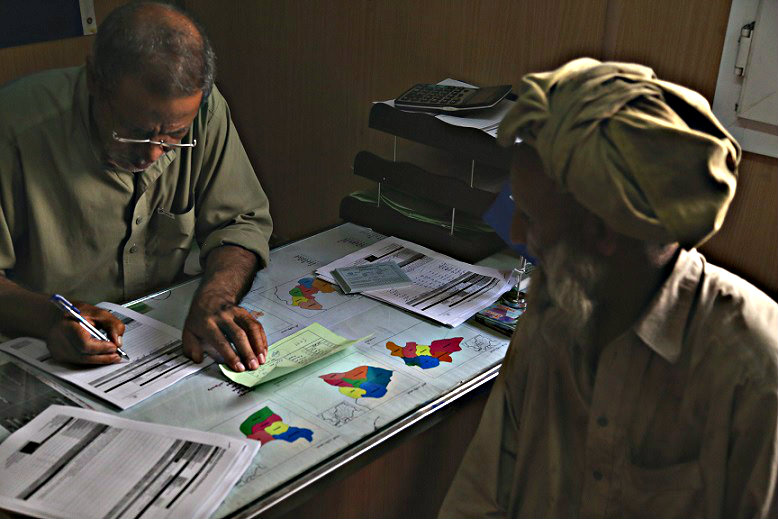

His exhaustion frequently bubbles to the surface as he is on the verge of tears. An IOM staff member extends a comforting hand in reassurance and directs Chenoor, as the head of his family, to the Department of Refugees and Repatriation’s registration office where his personal information is collected and he is issued with an entry document.

After this process is completed, IOM screening staff are on hand to assess his case to see if he and his family fall within well-established vulnerability criteria. Based on his advanced age and his wife’s condition IOM will provide him and his family with a post-arrival assistance package. Three kilometers from the border towards Jalalabad city, IOM maintains a Transit Center where undocumented returnees are registered for assistance, given a medical checkup with TB screening and vaccinations, a hot meal, there are limited overnight accommodation facilities for 30 families and a package which includes household and kitchen items and blankets plus a one-month food ration from the World Food Programme to help them start life anew.

(IOM’s Transit Center near Torkham where undocumented Afghan returnees can receive post-arrival assistance. 21 September 2016. Photo credit: ©N Bishop/IOM 2016.)

IOM currently assists 100-120 families a day (700-840 persons) or roughly 20 per of the daily influx from Pakistan through the Torkham crossing. On 16 September, as part of a broader UN emergency Flash Appeal, IOM launched its own appeal to the international community for an additional USD 20.9 million to scale up its presence on the border and at the Transit Center with improved services and distribution packages for 136,000 returnees by the end of the year.

November 15 marks a deadline set by the Pakistani government for all undocumented Afghans to acquire a passport and valid visa, although the chances of this happening on time seem slim to nil.

One of Chenoor’s main concerns ahead of winter is finding a home for his family. “Finding shelter for my family is my priority. Many Afghans are returning home now and it will be difficult for us to begin again especially before the cold and wet weather days in the winter. We need land and a place to live,” insists Chenoor as the worry on his face intensifies. At his age most men are well into retirement but he does not have the luxury.

The Afghan government has actively encouraged the undocumented to return to Afghanistan with promises of land allocations in spite of the ongoing conflict, lack of jobs and inflationary impacts the surge in returnees is already having on local rent and commodity prices. Nangarhar province now hosts up to 120,000 undocumented returnees or 90 per of the total in 2016. Rents have doubled in the past two months in several districts around Jalalabad while there has been a corresponding rise in fuel costs and a drop in daily wage labour. The sizeable returnee population is putting a strain on already stretched services with local area doctors recording over 80 patients per day.

At the Transit Center, Chenoor provides further detailed information as part of a Beneficiary Screening Assistance Form through an IOM staff member. He is given a beneficiary card and proceeds to bring his family inside the TC where they collect their food rations and household items. He is grateful for the assistance package with his daunting reintegration into life in Afghanistan looming overhead. His sons hoist their new supplies into their already crammed truck and the family drives off down the highway towards Nangarhar and an uncertain future.

(Chenoor Gul’s personal information is recorded on IOM’s Beneficiary Selection Assistance Form after which he is issued with an IOM beneficiary card and he proceeds to pick up a post-arrival assistance package. 21 September 2016. Photo credit: ©N Bishop/IOM 2016.)