Migrants, most of whom can't swim, wade towards a smuggler's boat on a Somali beach.

By. T. Craig Murphy, IOM Kenya, with Ismael Ali, IOM Bosasso

The closest geographic point from Africa to the Arabian Peninsula is a strait connecting the Gulf of Aden with the Red Sea known as “Bab-el-Mandeb”, which in Arabic means “The Gateway of Anguish.” Legend says that the name derives from the dangerous maritime navigation and the many lives claimed by the sea. At this point, it is only 30 kilometres from Djibouti to Yemen. Historically and contemporarily, this is the location from where large numbers of migrants move out of Africa for a variety of reasons.

Today, most of the migrants plying this route are from Ethiopia and Somalia, but other nationalities from the Horn of Africa compose these mixed migratory flows. A variety of factors – including security, legislation affecting migrant workers, difficulty or ease of crossing borders, viability of other irregular migratory routes, and weather – impact the migrant flows from the Horn of Africa to Yemen and other Gulf Coast Countries.

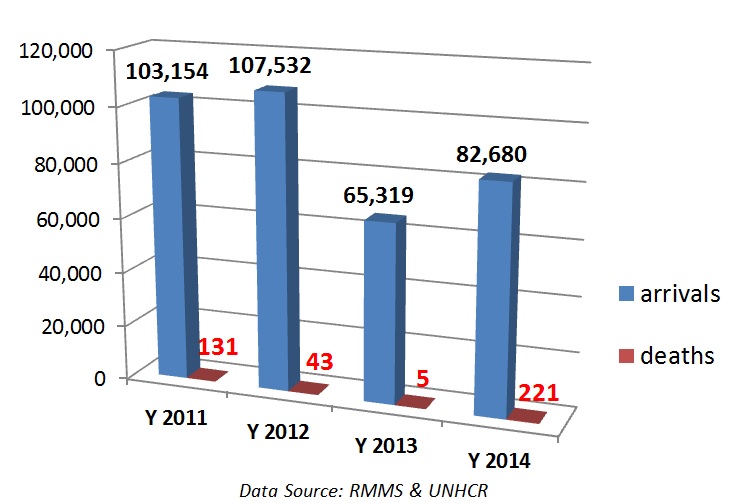

Graph 1 shows a summary of registered migrants and deaths at sea from 2011 to end of November 2014:

Graph 1: African Migrant Arrivals in Yemen and Recorded Deaths at Sea 2011 – 2014

These two data sets - registered arrivals and deaths at sea – are good indicators for the current situation of mixed migration flows from the Horn of Africa to Yemen. Analysis shows that the protection gaps and reports of mistreatment / abuse by smugglers and traffickers, as well as by government officials, persists – and in many cases have worsened.

In some locations across the Horn of Africa, there are “cultures of migration.” In such cultures, it is expected that the most able-bodied son or daughter should go abroad to earn money to support the extended family back home. This makes up a key profile of mixed migration flows – known as ‘economic migrants.’ This category of migrants voluntarily chooses to migrate, but this decision does not preclude them from the well-documented hardships and abuse that migrants experience along the way or at their final destination. Some migrants who depart through the services of a smuggler, find their situation changes and they become trafficked, by being deceived and kept in a state of exploitation. Refugees and asylum-seekers who are crossing borders to flee persecution are also included in mixed migration flows from the Horn of Africa. Though the motivation for leaving is varied and the intentions at the final destination are different, the diverse categorizations of migrants all face extreme vulnerability when migrating irregularly.

The International Organization for Migration has been responding to this migration crisis since 2009, through the implementation of a regional mixed migration programme. The strategy of the programme is to directly assist migrants, support governmental dialogue, provide awareness-raising materials to potential migrants, and foster coordination through the Mixed Migration Task Forces. As part of the direct assistance to migrants component of the programme, IOM works closely with governments across the region to support a series of Migration Response Centers (MRCs) in strategic locations along migration corridors. Currently, Migration Response Centers are operational in Metema and Mille, Ethiopia; Obock, Djibouti; Hargeisa, Somaliland; Bosaso, Puntland; and Haradh, Yemen. These MRCs allow for registration of migrants, referral for appropriate services (such as medical care), distribution of food and non-food items, and organization of Assisted Voluntary Return and Re-integration Operations.

In November of 2014, the Migration Response Center in Bosaso registered a 28-year-old Kenyan migrant named “Yusuf”[1]. Yusuf had returned to Somalia from Yemen by crossing the Gulf of Aden by boat. He was intending to return to his home in Mombasa, Kenya after spending four difficult years in Yemen as a migrant worker. Without valid documentation, he was detained by Somali authorities at the Bosaso port. Yusuf did not have the resources to continue on his journey and was not released until the authorities confirmed he had the means to reach Kenya by air. IOM offices in Somalia and Kenya helped Yusuf to return home to Kenya on 14 December.

As a Kenyan national, Yusuf is a much less represented nationality within the overall mixed migration flows. He left for Yemen from Mombasa by plane in 2010 in the hopes of finding a job. Yusuf never gained any sort of secure employment and only survived by washing cars. He says, “In Yemen I was jobless, and only received small money to cover the daily life.”

Yusuf goes on to describe the difficulties he faced as a migrant in Yemen as the political situation worsened in recent years. “When Yemen conflict started I was afraid to be killed, and there was no job even car washing. The life was difficult because I did not have any job there, and sometimes I used to be hungry for more than 2 days.”

Yusuf said that most migrants leaving the Horn of Africa for Yemen are “looking for jobs and better opportunity than in their country.” However, now, having been to Yemen and opting to return, he is aware of the risks and dangers for migrants, which he lists as: “death, harassment, detention, torture, and rape.”

Yusuf’s situation is not unique. His story is representative of the large mixed flows of tens of thousands of African migrants per year crossing the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden seeking a better life or reprieve from insecurity. With IOM assistance, Yusuf reached his home country of Kenya in a dignified and orderly way.

Upon arrival Yusuf stated, “I am very happy to arrive Kenya and thankful to IOM for helping me return home.” Others aren’t as fortunate. The statistics speak clearly. Thousands of migrants languish in vulnerable situations of detention or exploitation, unable to access the humanitarian services that IOM provides in the Horn of Africa and Yemen.

[1] His name has been changed to protect the confidentiality of the migrant