Remittances from Afghans working abroad and diaspora communities have long been critical for families and the wider economy. Along with so much else in Afghanistan, there is now uncertainty around this vital flow of finance.

Kabul – With Afghanistan’s financial system collapsing, remittances sent by Afghans abroad are more important than ever. Worldwide, there are 5.85 million Afghans living outside of their home country and their remittances serve as lifelines to their families and financial system, but as multiple catastrophes unfold in the country simultaneously, remittances too are in a parlous state.

Financial freefall

Afghans face a financial squeeze after the Taliban’s lightning-fast takeover of the country. The United States froze USD 7 billion of Afghan reserves. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) shut off financing to the country, including hundreds of millions of dollars in Special Drawing Rights, which can be converted into currency during times of crisis. Despite the resumption of banking in Afghanistan in late August, Afghanistan’s Central Bank can only access a fraction of its usual financing. This means that Afghan banks’ coffers cannot be easily refilled — ATMs have run out of cash and withdrawal limits have been put in place. In turn, prices for essential goods are soaring. There are fears of food shortages, higher inflation, and a slump in the currency — all resulting in an intensification of the humanitarian emergency across the country.

Remittances are crucial to Afghan families and the socioeconomic development of the country

Even before the latest crises, remittances were of paramount importance to many Afghan families and to the broader economy. Afghans working in Pakistan, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Turkey, Gulf countries, and further afield in Australia, Europe, and the United States, have been sending money to their families in Afghanistan for decades. With 5.8 million migrants from Afghanistan and diaspora residing abroad, their support to communities and families back home was indispensable.

In early 2021, a few months before the Taliban took over Kabul, Samuel Hall partnered with the World Bank to assess the impact of outmigration on women remaining in Afghanistan. One woman who took part in the research, Zeenat, lived in a rural village where job opportunities have always been sparse (names from the research have been changed). Zeenat’s husband had been working in construction in Saudi Arabia for almost a decade, sending home the equivalent of between USD 260 and 540 every two months. The remittances had allowed Zeenat to send their children to school, avoid loan sharks, and buy essential winter goods for the house. She was not alone: other interviewed women whose husbands were in Gulf countries (mostly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) received monthly or bi-monthly remittances ranging from USD 160 to USD 580 each time, an amount usually to be shared with the extended family of up to 30 people.

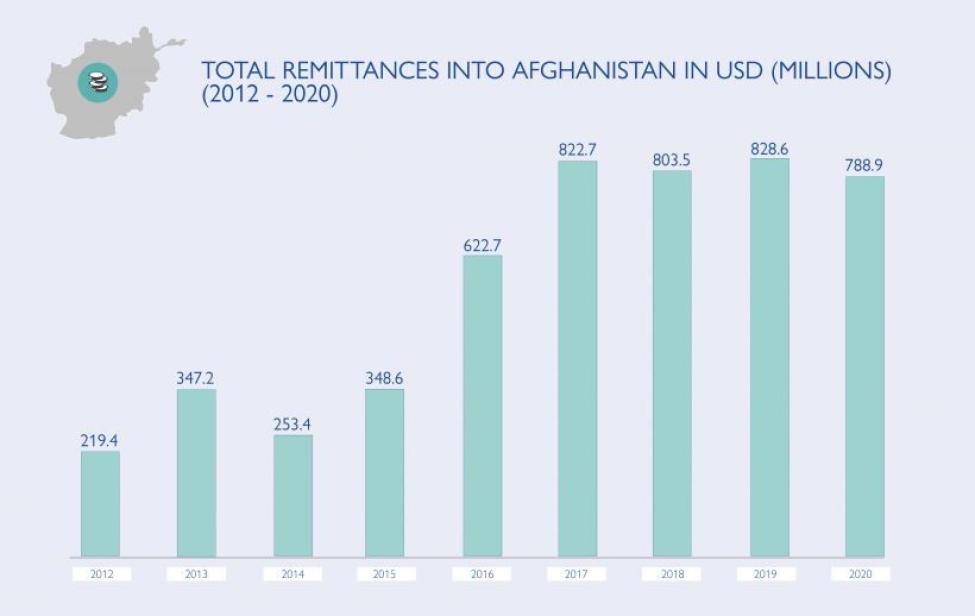

Together, remittances sent by Afghan communities abroad form part of a vast financial ecosystem. In 2020, formal remittances into Afghanistan totalled upwards of USD 788 million — approximately 4 per cent of Afghanistan’s total GDP. According to the 2016-2017 Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey (ALCS), remittances represent an income source for almost 1 in every 10 Afghan households. The money Zeenat’s husband sent back formed part of the flow of finances that allowed people within Afghanistan to buy food and pay rent.

“He sends money through hawala”

With Western Union and Moneygram temporarily halting services in Afghanistan and the operations of banks imperilled in the wake of the Taliban takeover, users had to find other means to get money into the country. But those official channels had never been the most important transfer mechanism. Before the Taliban regained authority in Afghanistan, only 15 per cent of Afghans had bank accounts and even fewer used their bank accounts regularly. Access to formal finance was also already highly gendered: Only 7 per cent of women across the entire country had access. While the formal banking system had been expanding in Afghanistan prior to the Taliban’s takeover, the informal sector and hawala system still dominated. The hawala system is an informal method of transferring money, including across borders, through a network of money brokers referred to as “hawaladars”. Some estimates suggested that 90 per cent of Afghanistan’s financial transactions ran through hawala, with over 900 providers operating across the country.

A few hours’ drive from Zeenat’s village, on the outskirts of a major city recently overtaken by the Taliban, Sana’s husband in Iran too had been sending remittances through the hawala system. “He sends money through hawala,” Sana explained, referring to her husband. “My brother-in-law or father-in-law collects the money from the city centre. I give them a list of items that I need at home, they purchase them, and give me the remaining money.” The hawaladars use their personal networks, based on trust, to transfer value between countries, charging commission and adjusting exchange rates to make money.

Before the Taliban takeover, the hawala system occupied a grey zone in Afghanistan — not entirely licit, nor illicit. Hawala has been linked to crime, money laundering and terrorism financing in Afghanistan and globally, but it is also crucial in remittances and money transfers where Afghans would not otherwise be able to access financial services. An Afghan returnee explained in a separate Samuel Hall study focused on the financial inclusion of displaced persons: “Hawaladars have many offices in all the provinces, and also internationally. You can find Hawala brokers in all the bazaars. Most remittances from migrants are transferred to Afghanistan this way, especially for the migrants who don’t have official documents to access banks or other transfer agents”. The use of informal channels to send remittances were impacted in many countries across Asia as pandemic-related restrictions meant informal, hawala-type money transfers were much less accessible or available as a channel to financial consumers and these restrictions pushed previously informal transfers toward more formal, or digital channels. It remains to be seen, however, how the Taliban takeover will impact these channels.

Uncertainty

Hawala underpinned the livelihood strategies of so many Afghans reliant on income from abroad. By its inherent nature, it is difficult to enforce network compliance with regulatory obligations. Indeed, most hawala transfers pass under the radar since no records of transactions are kept, with Skype, Viber or WhatsApp messages usually destroyed upon completion of transactions. For this reason, its use was discouraged by the Western-backed government. While it seems unlikely that the Taliban would try to shut down the all-important system, it seems likely that they will aim to exert greater oversight and may seek to extract taxes from it. But it is unclear whether the hawala system, which still relies on hard currency, can continue to function properly amidst the wider economic crunch. The lack of cash means Hawaladars may not be able to disburse funds as they did previously, in a similar fashion to cash-strapped formal banks. Those Afghans who do manage to leave the country may face difficulties finding work, while those left behind may face difficulties withdrawing funds sent their way.

This is (more) grave news in light of pressing humanitarian needs and drought-like conditions across much of the country. The United Nations warns Afghanistan could soon start to run out of food. As the need for remittances increased, the COVID-19 pandemic had already greatly reduced their frequency and amount. In a rapid Samuel Hall survey on the impacts of COVID-19, three quarters of the interviewed households receiving remittances had reported that this vital source of finance had dwindled as potential senders abroad were struggling themselves.

Zeenat’s husband was not able to send money for three months from Saudi Arabia during their lockdown, leading Zeenat to borrow money from a family member until her husband resumed work — and resumed sending remittances.

Working through uncertainty

Remittances are vital for many Afghans but many aspects of remittances into the country are not fully understood.

There is a need for higher quality data on the many different dimensions of remittances in Afghanistan. This includes data on remittance flow volumes, remittance corridors, remittance costs, average transaction size and channels utilized. Tracking the Taliban’s approach to Hawala, mobile money, and other financial services is also critical. There is a need for data on the dependency and uses of remittances as the situation in Afghanistan evolves, including the changing economic situation, the unfolding humanitarian crisis, the impacts of COVID-19, and any other issues influencing remittance flows and utilization.

There was already a lack of disaggregated data on remittances and financial services before the Taliban takeover of the country. Now, a better understanding of how Afghans can safely and sustainably access basic financial services such as savings and remittance transfers is even more pressing. What is the role of digitization during this time of turbulence? What are the main barriers to financial services, such as remittances, and how might they be overcome – whether it is for formal financial services or the widely used Hawala system?

More research on remittance-senders is also required. How will the outflow of refugees to neighbouring countries, and further afield, affect those Afghans who are already abroad, and the funds they can send home? What is the size of Afghan diaspora residing abroad and its willingness to engage in livelihood and humanitarian support to families in Afghanistan? If the scarcity of available cash continues, what could be the impact on cross-border mobility?

The emergency response can already better coordinate with Afghans who are abroad. The Afghan diaspora have been playing an essential role in supporting relatives and networks in Afghanistan for decades. In work with DEMAC in 2018, Samuel Hall analysed the role diaspora organizations play in contributing to emergency responses in crisis settings. How the Afghan diaspora continue to support their families in need back in Afghanistan, and how organizations can reinforce this support, will be a vital area of work moving forward.

Finally, integrating financial inclusion into the humanitarian response will support both agendas. United Nations agencies and non-government organizations have previously worked with mobile money platforms in Afghanistan to distribute cash quickly and securely. Afghans have also previously been able to use IOM and UNHCR documents to access low-risk, low-balance financial accounts and mobile money services. It is not clear at this point how the arrival of the Taliban will impact fragile gains in the use of formal and digital channels – indeed, some experts suspect that cash and informal channels may take on more importance in light of regulatory issues associated with the new regime. Adapting to the new circumstances, supporting Afghan families to send and receive money will be crucial during the unfolding economic troubles — with financial strains related to housing, food, and fuel already apparent. Many Afghans will need to be able to access humanitarian support and affordable financial services, including savings and remittances, to avoid predatory loans and negative coping strategies.

For Zeenat, her husband in Saudi Arabia, and her family, along with millions of others, what comes next for remittances is an essential question during Afghanistan’s swirling uncertainty.

Nicholas Ross is a Senior Project Lead for Samuel Hall, focusing on Afghanistan.

Stefanie Barratt is the Samuel Hall Pillar Lead for Data Standards and Analytics.

This blog was first published on the Migration Data Portal.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) or the United Nations. Any designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the blog do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers and boundaries. While the Portal has been made possible with funding from the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) Switzerland, its content does not necessarily reflect its official policy or position.

To know more about IOM's response in Afghanistan, click here.