By Paul Dillon

Ultra-marathoners Seth Wolpin and Sudeep Kandel relied on leg power and iron lungs to traverse a section of the famed Everest Mail Run; Theo Sinkovits thundered into the high country on his 350cc Royal Enfield motorcycle with a couple of pals.

Together with a small army of university teachers and students, they were helping IOM to assess exactly where survivors of the earthquakes that had rocked Nepal for the past three months have moved to, and what their immediate needs and future intentions are, as monsoon clouds settle over the Himalayan nation.

“To some people the data we collect for the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) might look like rows of numbers. But I see a very clear snapshot of what is going on out there, especially when compared with the results of previous assessments,” says Chandan Nayak, who led IOM’s DTM project through two rounds of data collection in Nepal in the eight weeks after the April 25, 7.8 magnitude quake.

A third round of data released this week (24/7) is based on assessments of 104 sites – less than a third the number that existed in the weeks after the quake – identified, containing 20 or more households, in 13 earthquake-affected districts.

IOM developed the DTM as a simple, insightful assessment tool – a six-page questionnaire – for use in emergencies worldwide. In Nepal, digital notepads replaced paper and pencil in time for the second round of surveys in May. The questionnaire takes 30 minutes to complete with the help of a key individual in each settlement location and can be easily adapted to local circumstances.

In Nepal it is being used to gather, analyse and disseminate information on the number and location of internally displaced people (IDPs) forced from their homes into temporary tent and tarpaulin settlements, and the availability of services in each location. The data guides the creation of timely, targeted response strategies by the government, IOM and its partners.

A useful communications component was added to the second and third rounds of the DTM that allows for critical information sharing with the people in those settlements; it takes the guesswork out of figuring out what key information people want to know and the best way to deliver it to them. A new “return intentions survey” in the third round is helping to better understand IDPs’ plans for the coming months and the hurdles they face rebuilding their lives.

The first DTM launched May 2, fed back information from 373 temporary settlement locations, where 93,500 people were living in the 14 most earthquake-devastated districts. In the second round, roughly 49,000 people were found living in the 77 settlement sites, where more than 50 families resided in the Kathmandu valley, where access is fairly straightforward.

That is not the case elsewhere. The UN estimates 315,000 of the 2.2 million people who have been forced from their homes cannot be reached by road and a further 75,000 cannot even be reached by air. The onset of the monsoon in June, floods and new landslides are further reducing access.

|

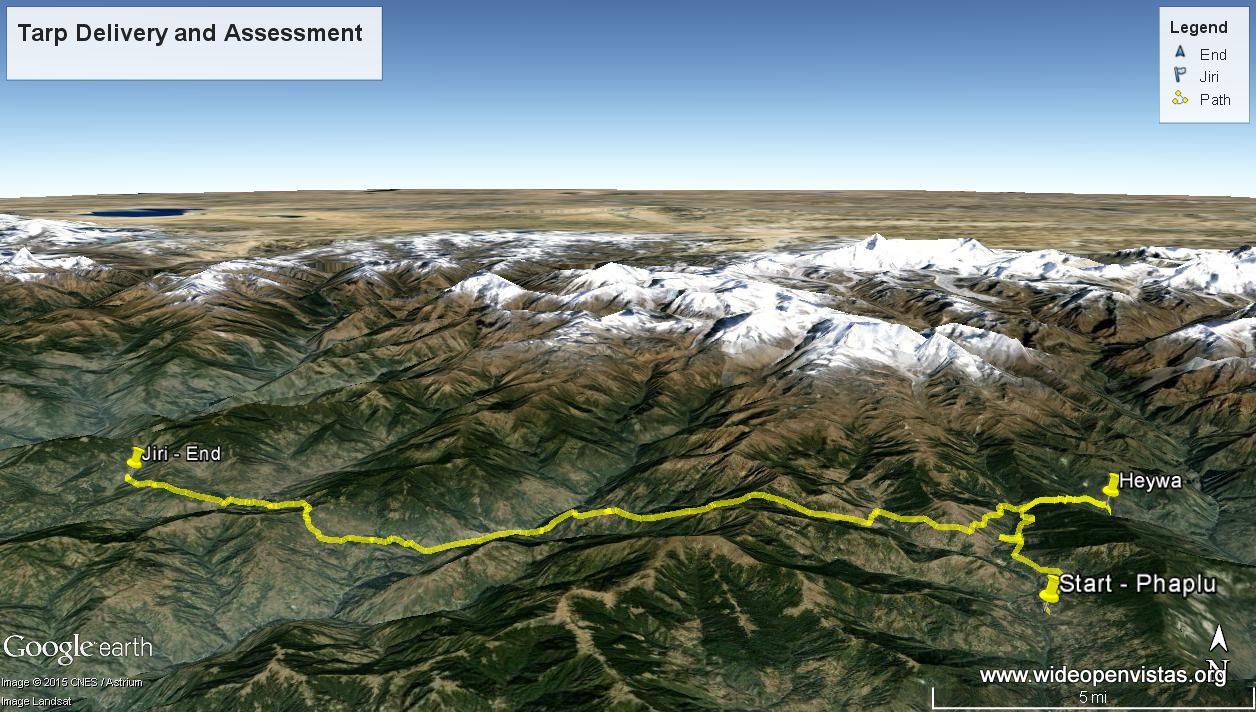

Seth and his Nepalese running partner Sudeep Kandel ran out of road in the town of Phaplu, in Solukhumbu district, northeast of Kathmandu in late May. They then hired six porters and later a yak, to carry 120 tarpaulins bought by his small, US-based NGO Wide Open Vistas (www.wideopenvistas.org) to the settlement of Heywa at 2,800 metres.

Rather than driving back to Kathmandu, over several days the pair then speed-hiked a section of the 319km-long mail run between the base camp at Mount Everest and the capital – the Nepalese version of the Pony Express – taking them through earthquake-ravaged areas hidden from the world’s eyes.

“In Heywa there was a lot of structural damage, cracked walls and foundations,” said Seth, a clinical associate professor at the University of Washington, who has been trail-running in Nepal for many years and who summited Everest in 2011.

“But once we got past Junebesi the next morning, every village looked like it had been bombed. You’d look down from the ridgeline and see small villages or clusters of homes that had been wiped out. There were a few tarps around… but for the most part these people are just trying to survive on their own.”

There’s little in the way of displaced people in those mountain areas, Seth says. People prefer to stay close to home, even if it’s nothing more than a pile of rubble.

“They’re moving into their cow sheds. They’re starting to frame temporary structures to get them through the monsoon, but really their focus is on farming,” he says. “They’re building temporary structures to wait out the monsoon, but they’ve got to get into the fields (to plant) their crops. You can’t rebuild while you’re doing that or worried about another earthquake that might wipe out your efforts.”

The situation is quite different north of the city of Pokhara, in striking distance of three of the highest mountains in the world.

After driving for 10 hours through scenes of utter desolation on the northwest side of the famed Lantang National Park, Theo and his two biker companions were forced back at Syapru Besi, Rasuwa district, where the police warned the road was impassable.

“We could see where the landslides had torn through and that rice paddies had slid down the valley completely,” Theo said. “So, no surprise that those who survived moved themselves out for there.”

As he collected DTM data in one temporary settlement of 450 people on the edge of a town, Theo and his companions were approached by a single woman who, like many people, was in dire need of proper shelter ahead of the monsoon.

“I was saying to this one man, ‘Hey, why don’t you just go and help her’… and he just looked at me and after a while he simply said, ‘I lost ten people from my family’. Sometimes you get so desensitized to things after seeing so much devastation…. that kind of conversation, it just sort of brings it all home… makes you wonder how you’d cope if it was your family.”

It’s the kind of conversation that gives a voice to the columns of data populating those DTM spreadsheets.